Who died in 2015, at the age of 80, Franco Farnè was one of the most relevant figures in ducati’s history. Armed arm of the engineer Taglioni, he was due to the survival in the motorcycle field of the Casa di Borgo Panigale in the dark years and the rebirth in the second half of the eighties.

We have dealt with him in the past, celebrating his feats as riderdriver, but defining what Franco Farnè was for Ducati, making an overview around the thousand facets of that jewel that has been his career inside the House of Borgo Panigale is an almost impossible undertaking.

Giving a definition of what Franco was for the Company would be really reductive, as it is not possible to classify its role in a single task,imprison its work in a single field, even if we tried to make the attempt to break the history of his career in various time periods. Farnè was pilot and also tester, manager of himself and other riderswas at the side of the

Ingegner Taglioni

when it came to putting models into production, really represented the push to compete, proving capable of being both the arm and mind of every adventure.

So we give up. We declare ourselves beaten at the start and choose to have a chat with him without the nagging of the rigor of historical continuity,going to snoop on a leopard spot in search of an anecdote, a curious story or, as the children do, to make us tell once again that story, which we may know, but which told another time, by him himself, continues to get passionate and excited.

Born on October 15, 1934, after working in a workshop where bicycles were repaired and in which he had the first contact with the mosquito and especially with the

Ducati Cucciolo,

after having made the boy of a baker and the welder, the world of engines definitively appropriates it: we find him engaged in a car workshop to seal the first oath of allegiance to an industry that will never give up again.

Father’s orphan, ducati’s career begins as follows: “It was my mother, an employee of the Borgo Panigale Company, who made an agreement for me to take over from her.” Franco was seventeen years old and was put to work in the rehearsal room, to take care of the Puppy and the Cruiser scooter. “My luck as a pilot – says Farnè – it was the endurance races that took place in those years: the Milan-Taranto and, above all, the Motogiro d’Italia.

These competitions were the showcase available to the Houses to present their products to the public. People were assiduous along the way and the bikes and riders were exalted by the emphasis of the image commentators who shot in the newsreel. Television, in fact, was not yet widespread in the homes of Italians and we were at the beginning of the period of mass motorization.

It was also vital that in the rankings, which the sports newspapers of the time reported in full, as many bikes as possible were included on arrival. “I was running around Bologna riding an Ibis 48 that I had pumped at 60 cc, I could easily stand in front of more powerful bikes and I was noticed by Eugenio Lolli, a foreman who also carried out the job of sporting director. I had applied to join the team that would play the first edition of Motogiro and I was satisfied, thanks also to the minute physique that would allow me to collect better on the bike.“

It is the beginning of a career that will be dotted with exhilarating stage victories and also frustrating breaks:“Yes, because often the bikes entrusted to me were those that had been used to try the entire route or had mounted experimental details.“

Franco’s commitment, like that of many runners of that type of races, is divided between the work in the Company and the competitions. It is precisely this dual value, which Franco manages to provide to Ducati, that will in a certain sense curb his career as a rider

He also began to race on the circuit, taking away the satisfaction of winning many races, and for three years in a row, from 1956 to 1958, he won the Italian Junior Championship: “Paradoxically, the fact that my work in Borgo Panigale was a valid help for engineer Taglioni delayed my transition to the Seniores category. He told me to be patient and that there riders drivers than me who had to do the category jump! My relationship with the Engineer, however, paid me back and allowed me a certain autonomy. Maybe I’d go to him and tell him That I had thought of a certain solution for an engine and he would give me permission to implement it, and then together analyze its actual validity. Or he told me that he didn’t think it would work, but that if I wanted to, I could try to put it in place.“

In the end, the passage riders “real” drivers arrived and Franco Farnè, on April 16, 1961, signed his most beautiful victory riding a Ducati. Born from the magical and far-sighted mind of Checco Costa, the Shell Gold Cup was held in Imola, aninternational race not included in the world championship in which, however, the best riders of the time took part.

There were the Hondas of Redman and Phillis,there was the German Degner with the MZ, the Bultaco with Cama and the Mondial by Francesco Villa. This is the story we want to hear, once again, from Farnè: “I had my own stable, the Farnè-Stassano, and my Ducati 125 Desmo. They wanted me to run with the long carter version, but I preferred my bikes.“

Only a month earlier, in the opening round of the Italian championship in Modena, Farnè had beaten everyone by also dubbing the third place finisher and finishing at mondial di Villa, second, 33″, repeating the feat in the second test of Cesenatico: Villa on the Mondial second spaced and unique not to end up dubbed.

Farnè was really on the ball: “The Shell Gold Cup trials were played in the rain and I had the best time on par with Degner. Phillis and Redman had hondas that were used in the British championship, less powerful than those used in the World Championship, but still fearsome. Race day didn’t rain. Immediately after the start, Degner was forced to stop to change the candle: I was first with Redman and Phillis behind. I was master of the situation and I could enjoy, with some fun, a funny scene. It happened that Degner, in stopping, lost a ride. A friend of mine, as well as a trusted man, noticed, the Engineer Taglioni did not. Once i left, the German threw himself head down in a furious comeback: my mechanic, when I passed, from the pits, with the fear that I could break and sure that Degner did not pose a threat, made me sign to slow down, Taglioni, instead, afraid of his return, believing him at full turn, made me sign to pull. It was beautiful and I would say to the German: ‘Come, come!’ I was sure, so much so that as I saw his silhouette approach, I lowered the average on the lap. The crowd had gone crazy, until the German bike broke and there was no more history!“

Australian Phillis, who would have given Honda his first world title in history that year, finished second by about half a minute. Franco, twenty-five, was referred to as the heir of Ubbiali,before a serious accident deprived him of the opportunity to continue his career.

At the same time, however, he began that of head of the racing department:still victories and a new relationship with the riders

“My favorite was Mike Hailwood, one capable of getting on a motorcycle after eight years and winning the Tourist Trophy, turning stronger than Agostini, despite being on a derived motorcycle as standard! Then I remember Spaggiari, from whom, ridera pilot, I sometimes took pay. – he says with a smile – Bruno was very strong and, although he never won the World Cup, he won some good races. Then there were Gandossi, also really strong, and Francesco Villa. In the endurance races, however, the ones that impressed me the most were the Spaniards: Canellas, Grau and even Garriga. They were able to run like one man, without being rivals to each other, trying to pull up even what was occasionally less fast between them.“

These were the years in which the acronym NCR was accompanied by exploits in endurance:“Nepoti and Caracchi were my friends. We started to have them build some chassis, on specifications of the racing department. I entrusted them with the work because, in times of lack of resources, it was better not to divert staff from production. It must be said that NCR grew up coming after me and that its men became good and famous because I carried them with me.“

Let’s go ahead and get to the advent of castiglioni management:“Ah, that changed! We really started doing some nice bikes. There was Massimo Tamburini and there was availability to run. Claudio Castiglioni was one who made his mark: he did as he said, period!“

Farnè remained in ducati’s racing department until the end of the 1990s, then the collaboration with Stefano Caracchi and Team SC: other victories and, out of all, that of Gianluca Nannelli in Imola in Supersport with the 749. It was 2005 and the smell of champagne soaking Franco, as radiant as we had never seen him on the podium, seems to feel it even now!

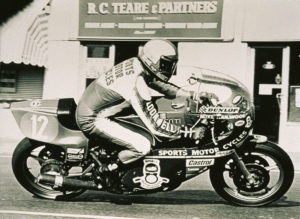

Photo by Paolo Grana and Farnè Historical Archive

SBK a Jerez: avanti tutta!

A Jerez de la Frontera, seconda tappa del campionato SBK, si ri-accende lo spettacolo con Ducati protagonista. Doppietta di Redding e secondo posto in gara 2 per Davies.

Mike the Bike: le eroiche gesta di Mike Hailwood

Il ritorno al TT di Mike Hailwood e le eroiche gesta del primo Campione del Mondo in Ducati, il pilota che per molti rappresenta il più grande di tutti i tempi.